- Home

- Máire T. Robinson

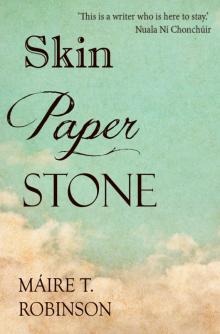

Skin Paper Stone

Skin Paper Stone Read online

SKIN PAPER STONE

First published in 2015

by New Island Books,

16 Priory Hall Office Park,

Stillorgan,

County Dublin,

Republic of Ireland.

www.newisland.ie

Copyright © Máire T. Robinson, 2015.

Máire T. Robinson has asserted her moral rights.

PRINT ISBN: 978-1-84840-3581

EPUB ISBN: 978-1-84840-3598

MOBI ISBN: 978-1-84840-3604

All rights reserved. The material in this publication is protected by copyright law. Except as may be permitted by law, no part of the material may be reproduced (including by storage in a retrieval system) or transmitted in any form or by any means; adapted; rented or lent without the written permission of the copyright owner.

British Library Cataloguing Data.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

New Island received financial assistance from The Arts Council (An Chomhairle Ealaíon), 70 Merrion Square, Dublin 2, Ireland.

About the Author

Máire T. Robinson lives and works in Dublin City. She holds a Master’s Degree in Writing from NUI, Galway. In 2012 she was nominated for a Hennessy Literary Award in Emerging Fiction. The following year, she won the Doire Press International Fiction Chapbook Competition. Her début collection of short stories, Your Mixtape Unravels My Heart, was published as a result. This is her first novel.

Acknowledgements

A massive thank you to Eoin Purcell for his belief in the book at an early stage, and to Shauna, Justin, Mariel and all at New Island for their help and support with everything.

Jack Harte and Clodagh Moynan; and to Conor Kostick and the members of the group that formed as a result of his workshop at the Irish Writers’ Centre who provided feedback on the first draft of the book – Hana, Michael, Rachel, Dearbhla, Jackie, David, Wes and Genevieve.

Thanks, as always, to Nuala Ní Chonchúir for her encouragament and kindness.

Dr Alison Forrestal of NUI, Galway for taking the time to meet with me and share her wealth of knowledge.

I’d also like to acknowledge some books that were invaluable during my research: The Sheela-na-gigs of Ireland and Britain by Joanne McMahon and Jack Roberts; Barbara Freitag’s Sheela-na-gigs: Unravelling an Enigma; and Grace Bowman’s A Shape of My Own.

All my friends for their support and interest along the way, especially Bridget Deevy, and my fellow historical site explorer, Benny Nolan.

A special thanks to my family: Catherine Robinson and Andrew Robinson, and to my extended family: Fran, Tony and all the Murphys. And last but not least, John Murphy – for everything.

Chapter 1

The baby’s cry was an accusation. Moments before, he was resting placidly in his mother’s arms. Now, in Stevie’s clutches, he wailed at an inhuman pitch.

‘There, there,’ said Stevie, in what she hoped was a comforting tone. The baby looked like a potato. An irate, screeching potato. It hadn’t been her idea to hold him, but there was no other option when Caitríona suggested it other than to smile and take the baby in her arms.

‘Aw, he’s just a little grumpy today,’ said Caitríona. She made a clucking noise, as though her newborn son were an errant chicken. ‘Who’s a grumpy boy? You are!’

The baby’s cries began to subside and Stevie gave Caitríona a relieved smile. Stevie was not surprised by the baby’s reaction. She had perfected her routine for visiting friends with newborns. She knew the right gift to bring, the right cooing noises to make, and the arranged smile that would convey her sense of wonder at her friend’s reproductive abilities. Stevie had everyone fooled. Everyone apart from the babies. It seemed that they sensed her discomfort, and wailed their protests accordingly.

Stevie had never bought into the notion of women ‘glowing’ during pregnancy. It was something people said, she suspected, to make them feel better: a consolation prize for the swollen breasts, varicose veins, constipation, and the all-round indignity of shuffling about like a giant watermelon on legs. It was only in looking at her friend now that Stevie realised how well Caitríona had, in fact, looked during the pregnancy. The contrast was stark. Caitríona was no longer Caitríona. If there were changeling children, perhaps there were changeling mothers too. Maybe the real Caitríona was away with the faeries glugging wine, chain-smoking, and throwing her head back in one of her unselfconscious throaty laughs, unaware that this other woman with a newborn in her arms had taken her place. This Caitríona had been ravaged, stretched, split open and stitched back together. She had given birth over a week ago, yet her stomach was still swollen in an effigy of pregnancy. There was an empty space, the former refuge where the screaming child was once silently curled up. Now there was nothing to fill it, like a plaster cast that keeps its shape long after it has served its function and been discarded from the recovered limb.

‘How are you finding Galway so far, Stevie?’

‘Yeah, it’s … well, it’s a nice change from Dublin anyway.’

‘Have you spoken to Donal since?’

‘Not really.’ Stevie shrugged. ‘There’s not a whole lot left to say. I heard he’s seeing someone.’

‘Already? Jesus, he didn’t wait long.’

‘Yeah. That’s him though. Can’t be on his own.’ Stevie tutted and rolled her eyes. ‘Fuckin’ eejit.’

Caitríona grinned and then sat forward and looked serious all of a sudden. ‘Are you sure you’re okay though?’

‘Me? Yeah, I’m grand. It’s none of my business what he does now.’ Stevie cleared her throat and looked up from the spot on the carpet that she’d been staring at. ‘But enough about me. What about this little fella? Have yous decided on a name for it? Jesus, sorry. I meant a name for him, his name?’

‘Oisín.’

‘Oisín, oh that’s lovely.’

A sure sign that she was getting older, Stevie had discovered, was that when her friends told her they were pregnant, the first thing she said was congratulations rather than oh fuck, what are you gonna do?

She smiled down at the bundle in her arms. ‘Hi, Oisín.’ At this, the baby’s roars started up again. Stevie held out the baby for Caitríona to rescue. Back in his mother’s arms, his cries began to peter out, until he was whimpering like a dog that had been kicked and couldn’t figure out why.

Caitríona unleashed a swollen breast puckered with blue veins, and offered it to the baby’s quivering mouth. Stevie looked at her cup of tea with a newfound interest and crossed her arms over her own, almost flat, chest. Silence. Then the noise of the baby suckling.

‘So when will yourself and Phil give him a little brother or sister?’ asked Stevie.

She intended it as a joke, expecting Caitríona to groan and say something like, Are you mad? Once was bad enough.

Caitríona smiled. ‘We’re going to start trying again as soon as possible.’

‘Really? That’s great,’ Stevie heard herself say.

Chapter 2

Joe Kavanagh turned into Buttermilk Lane. A busker’s tune floated up and reverberated off the high buildings, bouncing back to his ears, plaintive and sweet. Even though it was just some cheesy guy with a tin whistle, each note soared and sang out sad and true. He wasn’t one for the traditional music – the auld triangle, rebel songs, all that shite. Reminded him of home, where you couldn’t have a pint and the craic without it getting to that time of night when the auld fellas got sentimental and dewy-eyed with the pints on

them and the songs starting up. And them all shushing you to be quiet like you were at fuckin’ Mass or something. Nah, he couldn’t abide it.

Something about this change in the weather reminded Kavanagh of school uniforms and itchy collars: always that first week back when the sun would be scorching. Sunshine was a rare and blessed thing in Galway. It summoned the masses to outdoor worship. They walked along the Salthill promenade, squinty-eyed and joyful, lapping at their melting ice-creams. Dogs bounded with trampoline steps. Cats stretched in beams of sunlight and looked even more smug than usual. On sunny days, people liked to be close to water, and in the city there was a lot of it to go around. They sat on the grass beside the canal watching the eternal battle between duck and seagull. All manner of beatific worshippers sat by the river near the Spanish Arch – students, families with their children, crusties, winos, pill-poppers, and degenerates of every persuasion joined in holy union as they faced the sun. Tourists who had never experienced a winter in Galway sat in ecstatic contemplation. They had stumbled on some Celtic Shangri-La and were concocting plans to move to Galway immediately. Everyone felt connected under that sunlight, a palpable thing. On days like this, the city hummed.

Kavanagh saw the beggar-woman sitting in her usual spot at the end of the lane, hand outstretched, mumbling at passers-by: a living statue in a red raincoat, as much a part of the city as the buildings.

‘Howaya, Mary?’ he said, although he’d often walked past her without saying anything. ‘Lovely day for it.’ It tied in to this new feeling he had, walking around with a sense of pre-emptive nostalgia because things were starting to look different now that he knew he was leaving.

She looked up at him, her face hopeful, ‘Spare any money?’

‘No, sorry.’ He felt guilty then when he saw her face fall. ‘Ah, for fuck’s sake,’ he chastised himself. He shouldn’t have spoken to her in the first place. That was the problem with optimism – it created all sorts of headaches. He rooted in the pocket of his jeans and handed her two Euro.

‘Thanks,’ she said, pocketing the coin and giving him a brief smile. ‘Have you no paper money?’

He could feel the edginess creeping in as he cut through Eyre Square, and he had it in mind to head for a pint.

‘Kavanagh!’ a voice behind him called. He turned to see Maloney sitting on a low stone wall, a Buckfast bottle wrapped in brown paper clutched in his hands.

‘All right, man. What’s the craic?’ he said, sitting beside him.

‘Divil a bit,’ said Maloney, squinting. ‘What ya at yourself?’

‘Ah, fuck all.’ Kavanagh decided not to mention his plan to go for a pint. The last thing he needed was Maloney hanging off him.

‘Any smoke on ya? Serious drought on, so there is.’ Maloney’s words seemed to emerge through his nose rather than his mouth. They were punctuated by an occasional whistle that sounded like the breeze down the chimney of Kavanagh’s old house. Whenever he spoke to Maloney, he had the urge to grab him by the nostrils and force him to speak through his mouth.

Kavanagh shook his head. ‘Sorry, man. If I hear of anything, I’ll give you a shout.’

The late-August sun shone down on them, and Kavanagh closed his eyes and turned his face towards its warmth. He thought of Thailand. A beach. A hammock. The lap-lapping of waves and….

‘Fuckin’ pigeons. Rats with wings, hah?’ said Maloney, nudging Kavanagh out of his reverie with a sharp elbow to the shoulder. He opened his eyes in time to see Maloney stand up and aim a kick at a mottled grey bird with his metal-capped boot. The pigeon leapt from the discarded punnet of curry-cheese chips it had been pecking at and landed a foot away on the grass, eyeing Maloney with one beady eye and then eyeing the punnet. Kavanagh shielded his eyes from the sun and looked at the offending bird. Its feathers gleamed in the sunlight like spilt petrol.

‘Look at it. Fuckin’ rotten yoke,’ said Maloney, as he spat in the direction of the bird.

‘Jesus, Maloney. It’s only a pigeon, for fuck’s sake. Keep your hair on.’

Maloney drank from the bottle again before offering it to Kavanagh. A tightrope of saliva still joined the bottle and Maloney’s mouth.

‘Ah no, you’re all right, thanks.’

Maloney shrugged and took another swig.

‘Lookit, he’s still got his eye on those chips. The fucker.’ Maloney took a step towards the bird, who looked up at him but didn’t budge. ‘You’ll not get these,’ he said, stooping down to pick up the container. The pigeon hopped off a few steps and looked back as if deciding on something, before taking off and flapping into the distance. The two men stared after it until it became a dot in the sky. It occurred to Kavanagh that a stranger passing by might look at him and Maloney and see no difference between them – two straggly wastes of space knocking back cheap booze in the afternoon – but he knew he wasn’t like Maloney. Not a bit. No, he was a man who was going places.

Maloney shoved the chips under Kavanagh’s nose. ‘Here, d’ya want one?’

‘Fuck off, Maloney,’ he said, swatting the hand away.

Maloney shrugged, then threw the punnet in the nearby bin and wiped his hands together with a satisfied clap. ‘Well, don’t say I never give ya anything, ya cunt.’

Kavanagh sighed. ‘Here, Maloney, have you heard of any work going?’

‘Work?!’ spat Maloney, as if the word offended his sensibilities. ‘Fuck no. Are ya not signing on, like?’

‘Ah yeah, I am. I’m doing a kind of apprenticeship, you know, but it doesn’t pay. I’m learning how to do tattoos. You know the place on the docks?’

‘Oh ya, it’s that duck place, is it?’

‘Duck place? Jesus, Maloney. Did they not teach you any Irish in school?’

‘Ah, they did, yeah.’ Maloney grinned. ‘An bhfuil cead agam dul go dtí an leithreas?’

‘It’s dúch, not duck. It means ink.’

‘Oh, right, ya,’ said Maloney. ‘So, are you actually doing the tattoos, like?’

‘Well, not yet, but eventually, yeah.’

‘I got one done in Santa Ponza a few years ago.’ Maloney rolled up his sleeve and showed Kavanagh his arm. Kavanagh squinted at an indistinguishable faded green blob.

‘Here, what is it?’

‘It’s a fucking shamrock.’

‘Oh yeah, course it is. I see it now.’

‘Yeah, all the lads got them. Phelan was fucking out of it, man. He got it on his arse.’

Maloney laughed at the memory, hocked up some phlegm and spat it on the ground. It looked more like a shamrock than the thing on his arm.

‘We’d some craic on that holiday.’

‘Yeah? I’m heading off myself soon. Thailand. Just need to get some cash together first.’

‘Thailand? Is it the ladyboys you’re into or what?’ Maloney snorted.

Kavanagh put his head in his hands. ‘Jesus, I have to get out of here. Seriously. It’s depressing.’

‘Here, sell some more of that weed and you’ll have the money like … that.’ Maloney tried to click his fingers, but no sound emanated. He tried again, frowned at his fingers and then looked at Kavanagh, a sly smile creeping onto his face. ‘Oh sorry, man. I forgot. Sure you can’t be doing that any more what with Pajo an’ all coming after ya.’ Maloney gestured towards Kavanagh’s eye, where a purple bruise was faintly visible, fading to a dull yellowish colour at the edges.

‘This? Walked into a door, Maloney.’

‘I heard it was good shit.’

‘Who told you that?’

‘Ah, no one. Just I heard it was better than Pajo’s fucking dried-up twigs and sticks, is all. Can you sort us out with some?’

‘I dunno where you’re getting that from, Maloney. I wouldn’t know anything about that.’

He looked at his wrist, althou

gh he wasn’t wearing a watch. ‘Listen, I better be heading off anyway, yeah? I’ve to meet someone. Take it easy.’

‘All right, man. Sure I might see ya later for a pint.’

‘Yeah, grand,’ said Kavanagh as he headed off. ‘Ya will in yer shite,’ he muttered.

‘Sound, man, sound.’ Maloney’s nasal farewell floated after him on the breeze.

That was the problem with Galway, he thought to himself. Too many shifty fuckers that you shouldn’t even be giving the time of day to. Fuck it. He’d walk around and he might bump into someone else to go for a pint with. There was always someone to go for a pint with.

*

Kavanagh stumbled inside and headed straight for the kitchen. He could hear the low, familiar noise of his housemates, Gary and Dan, playing Grand Theft Auto. The place stank of weed. It wouldn’t even occur to them to open the bloody window. Pair of clowns. He grabbed a can of beer from the fridge and popped it open, taking a long drink. Then he saw it on the kitchen table: the brown parcel that was addressed to him. He lunged for it and tried to pry open the cardboard box that was sealed shut with layers of brown tape. He squinted at it and tried to get his eyes to focus. After fumbling with it and cursing at it for a spell, he found the edge of the tape and started to peel it back, but it broke off in his hand.

‘Fuck!’ he cried impatiently.

‘All right, Kav?’ came a lazy voice behind him.

He turned to see Dan standing in the doorway eating a packet of crisps.

‘Oh yeah,’ Dan pointed at the parcel. ‘That arrived earlier. I signed for it.’

‘Cheers, Dan.’ Kavanagh grabbed a sharp knife from the block on the counter and sliced through the tape.

‘Very discreet packaging for a dildo supply shop.’

Kavanagh shook his head. ‘I am surrounded by idiots.’

‘Speaking of idiots, are you having some trouble opening that box there, Kav?’

Skin Paper Stone

Skin Paper Stone